It’s natural for investors who have only been following the market for the past 10 or so years to think the growth style is the default investment winner. This perspective could be attributed to the prevailing trends and achievements witnessed over this relatively short period, such as the remarkable surge of technology companies’ stock prices, the rapid expansion of e-commerce giants, and the proliferation of innovative startups that have gained substantial market valuations.

Tesla rocked it with a mind-blowing 13,198% share price leap from 2012 to 2021. £1,000 then? Now £131,980. Netflix? Up 5,348% in a decade. Facebook? A 1,428% growth.

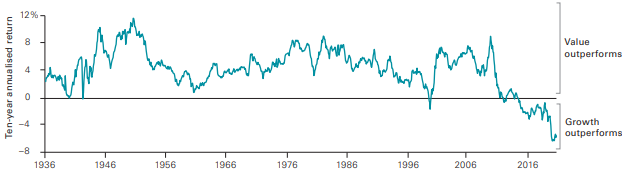

Over the course of a century, the intricate dance between value and growth investing has seemed to be a defining rhythm in financial markets. Yet, according to a decade-by-decade scrutiny over the past hundred years, the tug of war has never really existed. As you can see in the chart below, value has always had the upper hand.

Data Credits: Vanguard

But the real question that arises here, is whether value investing is the ultimate long-term winner, or if a slight shift in trend is all growth stocks need to outperform value for decades to come.

By definition, value stocks are those that trade below their intrinsic value, based on fundamental metrics like price-to-earnings (P/E), price-to-sales (P/S), or price-to-cash flow (P/CF) ratios. These stocks typically have lower growth rates, higher dividends, and more stable earnings than growth stocks.

Growth stocks, on the other hand, have high growth potential in terms of revenue, earnings, and cash flow. Growth investors look for stocks that are expected to outperform the market average over time, because of their innovative products, disruptive technologies, or competitive advantages.

Proponents of value investing often emphasize the enduring principles endorsed by Benjamin Graham and Warren Buffett. They argue that the concept of a “margin of safety” inherent in value investing provides a solid foundation for long-term success. By focusing on stocks trading below their intrinsic value, value investors seek to minimize downside risk and capitalize on eventual market corrections, a strategy epitomized by the Piotroski Score, Graham Number, and Price-to-Book Ratio. The historical existence of a “value premium,” where value stocks have outperformed growth stocks over time, provides empirical support for the enduring nature of value investing’s principles.

There are a few important points to note about this concept:

⭕A lower price doesn’t always mean you’re getting a good deal if the underlying value is weak. On the other hand, a higher price may be justified if the value is substantial.

⭕Investors should assess the fundamentals of an investment, such as its earnings potential, financial health, competitive position, and growth prospects, to determine its intrinsic value.

⭕Successful investors, like Warren Buffett, often seek investments that are undervalued by the market (where the price is lower than the perceived intrinsic value) because they believe that, over time, the market will recognize the true value, leading to potential profits.

Comparison of growth and value investing

The Fama-French Three-Factor Model

One way to compare value and growth stocks is to use the Fama and French three-factor model. It is a widely used asset pricing model that explains the returns of a portfolio using three factors: market risk, size risk, and value risk. The model was developed by Nobel Laureate Eugene Fama and researcher Kenneth French, who found that value stocks outperform growth stocks and small-cap stocks outperform large-cap stocks on average .

The Fama and French three-factor model can be expressed as follows:

R = Rf + Bm(Rm – Rf) + Bs(SMB) + Bv(HML) + e

where:

- R is the portfolio return

- Rf is the risk-free rate

- Bm is the beta coefficient for market risk

- Rm is the market return

- Bs is the beta coefficient for size risk

- SMB is the small minus big factor, which measures the difference between the returns of small-cap and large-cap stocks

- Bv is the beta coefficient for value risk

- HML is the high minus low factor, which measures the difference between the returns of value and growth stocks

- e is the error term

According to the Fama-French three-factor model, value stocks tend to have higher returns than growth stocks over the long term, because they have higher exposure to the value factor. This means that value stocks are riskier than growth stocks, and investors require a higher compensation for holding them.

You can measure the exposure of a stock to the value factor is to use the book-to-market ratio (B/M), which is the inverse of the P/B ratio. The book value of a company is its total assets minus its total liabilities. The market value of a company is its share price multiplied by its number of shares outstanding. The B/M ratio compares the book value of a company to its market value. A high B/M ratio indicates that a company is undervalued by the market, and vice versa.

The Momentum Factor

The momentum factor is another popular metric for comparing value and growth stocks. Momentum investing is based on the idea that stocks that have performed well in the recent past are likely to continue performing well, and stocks that have performed poorly are likely to continue underperforming. This concept is grounded in behavioral finance theories, which suggest that investors tend to underreact or overreact to new information, leading to price trends.

Growth Stocks: Growth stocks are expected to have positive momentum. Investors look for stocks that have exhibited strong recent price increases, indicating robust earnings and revenue growth. Positive momentum in growth stocks reinforces their attractiveness.

Value Stocks: Value stocks, on the other hand, might exhibit negative momentum if they have underperformed in the recent past. This could be due to market undervaluation, but investors need to carefully analyze whether the negative momentum is a temporary anomaly or a long-term concern.

Momentum investing, which relies on recent past performance as an indicator of future returns, has its drawbacks when applied to the comparison of growth and value stocks:

- Reversion to the Mean: One significant limitation of the momentum factor when comparing growth and value stocks is the tendency of stock prices to revert to their mean values over time. Stocks that have recently performed exceptionally well may be overvalued and likely to revert to their mean returns. Underperforming value stocks may have the potential to rebound, leading to a misleading assessment if momentum is the sole criterion for comparison. R_t = μ + ε_t, where: Rt represents the stock’s return at time, μ is the mean or average return, ϵt is a random error term.

- Volatility and Risk: The momentum factor tends to neglect the importance of risk and volatility when comparing growth and value stocks. The Sharpe Ratio, a widely used measure of risk-adjusted return, highlights this limitation. Sharpe Ratio = (R_p – R_f) / σ_p, Where: Rp is the portfolio return, Rf is the risk-free rate, and σp is the portfolio standard deviation (volatility).

- Market Sentiment and Behavioral Biases: Momentum investing is based on the assumption that investors’ behavior is predictable, but this overlooks the influence of market sentiment and behavioral biases. Behavioral finance theories suggest that investors can be driven by emotions, leading to irrational decisions. For instance, the disposition effect, where investors tend to sell winners too early and hold onto losers too long, can distort momentum signals.

Who will reign supreme over the next 100 years?

Let’s start by acknowledging that a century is an incredibly long time. Within the expanse of a century, economies will rise and fall, technologies yet to be conceived will reshape industries, and societal values will evolve. Trying to predict financial outcomes over such a vast period is a truly humbling task.

Exponential Growth and its Limits

One key consideration in assessing the potential of investing is the concept of exponential growth. Growth stocks often represent companies with innovative technologies or business models that have the potential to grow exponentially for a period. However, it’s important to recognize that exponential growth cannot continue indefinitely. As companies mature, their growth rates are likely to slow, and they may eventually reach a saturation point in their respective markets. This phenomenon is known as the “S-curve” of adoption and is a fundamental concept in assessing the longevity of growth stocks.